Every Currency has an Exchange Rate that determines its Value when compared against the Value of another Currency. This is best demonstrated by the Price of conversions between one Currency to another. If one wishes to know how much their Geld (or, in most cases, Kapital) is worth in another Currency, begin by determining the Exchange Rate. That equation is:

Exchange Rate = (Starting Amount of Currency A) / (Total Amount of Currency B)

And if one knows the Exchange Rate and the amount of Geld that they have, but wish to know the final amount in the other Currency, the equation reads as:

Total Amount (Currency B) = Starting Amount (Currency A) * Exchange Rate

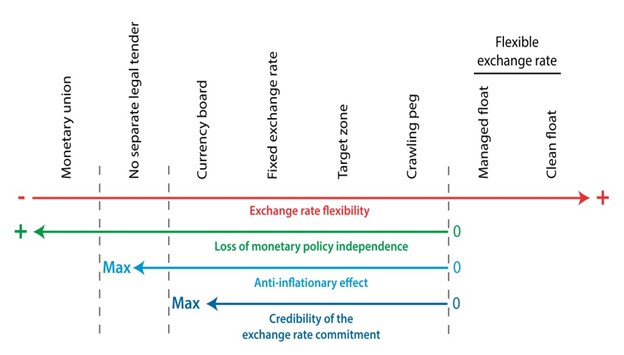

The Work-Standard still operates according to those same equations. This is because the Value of a Sociable Currency, a Currency pegged to the Work-Standard, is being compared against the Value of another Currency. That other Currency may be another Sociable Currency or it could be another type of Currency altogether. The real differences begin with the monetary policies that ultimately govern Exchange Rates. The Death of Bretton Woods did not just give birth to the Debt-Standard and the trillions of US Dollars of Schuld (Debt/Guilt) plaguing whole economies. In addition to the questions of Market/Mixed Economies and Planned/Command Economies, there is also the question of choosing between “Fixed Exchange Rates” and “Floating Exchange Rates.” As this following diagram demonstrates:

The difference between Fixed Exchange Rates and Floating Exchange Rates is far more than a political question of whether the Council State determines the exchange rate under the Intents of Command and Obedience or the Incentives of Supply and Demand. Insofar as the Work-Standard is concerned, there is the financial question of tackling the “Impossible Trinity.”

The Impossible Trinity refers to the ongoing dilemma within Exchange Rates where Currencies must balance between Sovereignty, Stability, and Mobility. In its simplest form, the Impossible Trinity insists that a Currency can emphasis two of the three attributes at the cost of sacrificing the advantages of the third attribute.

- “Sovereignty” is whether a nation issuing its own Currency is able to set Exchange Rates on its own terms. Either the Value of the Currency is determined by its issuing Financial Regime, influenced by another Currency or else issued by another Financial Regime like the European Union in the case of the Euro.

- “Stability” is whether the Currency in question can maintain its Value without too much Currency Depreciation/Appreciation. Either the Value of the Currency is considered operating on a Fixed Rate or else on a Floating Rate.

- “Mobility” is whether the Currency is allowed to move freely across international borders without any controls and taxes. Either the Currency is allowed to circulate across international borders freely without too much Currency Depreciation/Appreciation or else there are controls in place to prevent any large fluctuations in its Value as in the case of the Chinese Renminbi.

Currencies allowed to float are able to have more flexible exchange rates by means of the Incentives of Supply and Demand. While a Floating Exchange Rate maintains the sovereignty of a nation’s ability to issue its own Currency, the Currency is not guaranteed to survive sudden, sustained rates of Currency Depreciation/Appreciation. Conversely, nations lose their monetary sovereignty when they join a monetary union like the European Union, which makes them less vulnerable to Currency Depreciation/Appreciation.

What happens when a Currency tries to be stable, sovereign and mobile at the same time? The result is a financial crisis associated with the Currency in question. The Mexican Peso Crisis of 1994-1995, Asian Financial Crisis of 1997-1998, and the Argentinean Financial Collapse of 2001-2002 are historical examples, each one demonstrating the consequences of applying all three.

Before any serious critique of the Impossible Trinity can be made from the purview of the Work-Standard, an investigation into its technical origins is needed. In essence, the Impossible Trinity finds its basis at the height of Bretton Woods during the 1960s vis-à-vis the “Investment/Savings-Liquidity Preference/Money Supply-Balance of Payments Model” (IS-LM Model), otherwise known best as the “Mundell-Fleming Model.” Economists Robert Mundell and Marcus Fleming devised the model by building upon the IS-LM Model to apply for Liberal Capitalist Market and Mixed Economies. The IS-LM Model that the Mundell-Fleming Model is based on John R. Hicks’ 1937 economics journal article ““Mr. Keynes and the Classics: A Suggested Interpretation,” which found its basis in John Maynard Keynes’ General Theory. Understanding the Mundell-Fleming Model entails also understanding the IS-LM Model.

The Investment-Saving Curve of the IS-LM Model refers to the Supply and Demand for the production of goods and services. Its equation reads as:

Production (Y) = Consumption * Production — Taxes [C(Y-T)] + Investments (I) + Government Spending (G)

The LM curve refers to the Supply and Demand for Kapital according to the Interest Rate and the Output of Kapital. Its equation is:

(Money Supply (M)) / (Price Level (P)) = Money Demand (Interest, Production)

The Mundell-Fleming Model builds upon the IS-LM Model by including the “Net Exports” of goods and services and their “Price Level” in another Currency. The Model is best for understanding Liberal Capitalist Market and Mixed Economies, but not suitable for understanding Socialistic Planned and Command Economies. Moreover, both Models are impractical for use with the Work-Standard due to relying on financial and economic paradigms more attuned to Socialism.

Given the three attributes of the Impossible Trinity and the two Models that have provided them their political legitimacy, it is conclusive to argue that the Work-Standard operates differently within the parameters of Fixed and Floating Exchange Rates. The reasoning for this is tied to the fact that the Value of a Currency pegged to the Work-Standard is guaranteed to a Fixed Exchange Rate backed by the Actual Arbeit of the Planned or Command Economy. Additionally, the Work-Standard requires a Currency’s issuing nation-state to wield the national sovereignty necessary in setting the Exchange Rates. This leaves the question of the movement of said Currency across international borders, which are nonetheless dependent on Real Trade Agreements (RTAs).

The question of whether to impose controls on the movement of Currencies across international borders is a technological matter inasmuch as it is also financial and geopolitical. The Work-Standard provides justifications for imposing greater flexibility in terms of monetary flows for the Council State. While the Totality can technically move Actual Geld across international borders with relative ease, the State will always be the final authority on deciding the Exchange Rates and whether there will be FECs (Foreign Exchange Certificates) in circulation or not. This is because the Council State is responsible for handling all matters related to International Trade.

Categories: Compendium

Leave a comment