“Cold War geopolitics, in short, was a powerful and pervasive political ideology that lasted for over forty years … Strategic analysts have been searching ever since for a new global drama to replace it, launching ‘the end of history,’ ‘the clash of civilizations’ and ‘the coming anarchy’ among others as new blockbuster visions of global space, only to see them fade before the heterogeneity of international affairs and proliferating signs of geographical difference. Political leaders have struggled to articulate visions of the new world (dis)order amidst the overwhelming flux of contemporary international affairs (Ó Tuathail and Dalby 1998/2002:pp. 1–2).”

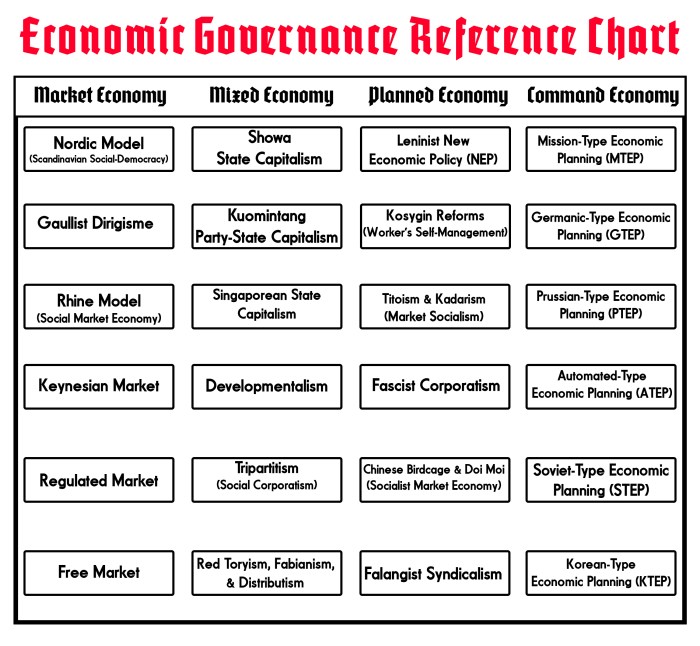

The purpose of Part II is to focus on the philosophical development of State Capitalism insofar as it has been understood since the last century or two. The concept is so broad that it deserves its own Part before proceeding to any further discussions in Parts III and IV. The discussion here pertains to the implications of what State Capitalism entails and why it, in both theory and practice, resembles a crossroads to an infinite number of possibilities.

Every nation that tried to abandon Neoliberalism always had to start somewhere. This is an historical reality that has sadly been lost to far too many people claiming to oppose Neoliberalism here in the Western world. Some are inclined to believe that one could immediately go from Neoliberalism to either Syndicalism, Corporatism, or Socialism overnight. The problem with this sort of thinking is one loses sight of what happens between abandoning Neoliberalism and adopting another Ideology. The journey itself is just as important as the destination.

Thus, the nations that abandoned Neoliberalism throughout the 20th century consistently started with some kind of State Capitalism before moving on to another Ideology. The German Reich embarked on State Capitalism during the latter half of the 19th century before attempting Socialistic ideas in the First World War. The Soviet Union, as it is already well-known, implemented State Capitalism as part of Vladimir Lenin’s NEP (Novaja Ekonomičeskaja Politika; New Economic Policy). Fascist Italy employed State Capitalism as a means of creating a precedent in which an empowered Business Community and an equally empowered Organized Labor would form a triumvirate with a Corporate State befitting of State Corporatism.

We find similar parallels in Imperial Japan and the People’s Republic of China. Some of the best features of the post-1945 Japanese economy, the ones which were more or less upended by the Lost Decades, had their origins in attempts at establishing State Capitalism back in the 1930s. In Mainland China, State Capitalism was introduced in response to the failures of the Great Leap Forward but differed significantly from the contemporary Socialist Market Economy.

In all of those examples, there was a recurring belief that any genuine alternative should distance itself as much as possible from the current Liberal Capitalist economic paradigm. Doing so meant acquiring the required resources, manpower, and overall economic and financial firepower. Once the required necessities were at hand, as soon as everything was stabilized, only then can actions be made to adopt another Ideology. Since the fundamental aim is to promote the vitality and prosperity of the Nation, it became inevitable to insist on a “State presiding over a Community of Vocational Civil Servants” as the primary driver as opposed to a “Civil Society and its Market of anonymous Private Citizens.”

From the perspective of the State Capitalist and the Social Capitalist, the proposals for Syndicalism, Corporatism or Socialism will be met with skepticism, if not outright uncertainty and unfamiliarity. The Syndicalist Economy enables a Syndicalist State to put labor unions of varying affiliations in charge of Enterprises, the Socialist Economy encourages the Council State to promote the Economic Socialization of the State Enterprise and the Social Enterprise, the Corporatist Economy emphasizes collaboration by a Corporate State. Economic ideas which correspond to the Nation being either Confederal, Federal, or Unitary respectively.

The problem is that not everybody knows how to approach these ideas and how to best convey them to the State Capitalist and Social Capitalist. The former thinks the rest of the readership of The Work-Standard (3rd Ed.) are in favor of ideas which have never been done before with the Work-Standard and the historical record only describes the economic performances of various Syndicalist, Corporate and Council States without it. The latter, meanwhile, believes the rest of the readership are radicals insofar as they are content with ensuring that everyone should have a chance in the here and now. Yet, their skepticism is different from those of the Liberal Capitalists, who have their own ideological positions which prevent them from entertaining such economic ideas too readily.

Consider the ongoing state of the true “American Right” and the true “American Left” insofar as neither can claim to be Jeffersonians in charge of the Democratic-Republican Party. Many do not realize this, but any serious and genuine implementation of their ideas will inevitably require some form of State Capitalism rather than Liberal Capitalism. Suppose for a moment that the Hamiltonians on the American Right and the Hamiltonians on the American Left have succeeded in establishing a new American Center. They have the political power to do what they wanted to do when the Jeffersonians were in charge of the Federal and State Governments. Will they have the knowledge, skills and abilities to govern the National Economy as well as the National Government? How about the Financial Regime, the National Educational System or the Digital Realm?

If State Capitalism were to be realized here in America, will the Intent be to overcome the prevailing Liberal Capitalist consensus among the Jeffersonians of the Democratic-Republican Party? Or will the Intent be to bolster Neoliberalism and the Empire of Liberty insofar as both have since taken significant losses to their credibility since the 2000s?

Nowhere else except State Capitalism are these questions going to be asked. That is because State Capitalism represents a sort of no-man’s land where there are countless different possible directions to take. A Nation that transitioned to State Capitalism could always return to Liberal Capitalism just as easily as it could transition toward Conservative Socialism. These are not a question of Incentives, but a question of Intents.

Vladimir Lenin realized this when it came to his NEP, creating distinctions between a “State Capitalism for Neoliberalism” and a “State Capitalism against Neoliberalism.” The former leads back to Neoliberalism, the latter away from it. The process by which it occurs is determined by who is in control of the National Government. Even among Populists agitating for “Economic Nationalism” or “Democratic Socialism,” the rhetoric is always the same: the all-pervasive influences of Kapital and Schuld have become too burdensome for countless everyday people. That economic life should be driven by actual Economic Organizations rather than Financial Markets and Fractional-Reserve Banking Systems.

The Intent is always important in ascertaining why specific actions are to be taken. Why has “Industrial Policy” and “Protectionism” become important topics within the literature of today’s Hamiltonians on the American Right and American Left? Is the Intent of these measures to overcome the Neoliberal paradigm in favor of a Post-Liberal one? Or is the Intent to preserve the current state of affairs and bolster the Empire of Liberty? As long as the answers to these questions remain fixed on pure Economism (as in, higher wages, more social benefits, less hours in the workday and so forth), no definitive judgment can be made at this time.

Categories: Blog Post

Leave a comment