As established earlier in a preceding Entry, the Soviet Union’s accounting system was designed to accommodate the Economic Planners. The methodology enabled Enterprises to maintain and create records in support of Soviet-Type Economic Planning (STEP). It came into being between the New Economic Policy and the 1st Soviet Five-Year Plan. It may have tried to derive aspects from the Marxist Labor Theory of Value (LTV), but it nevertheless represented an attempt at articulating an alternate conception. One may be inclined to ask if there was a Chinese Maoist approach to accounting that emerged in the People’s Republic of China under Mao Zedong. In essence, the Maoists favored a modified version of the Soviet accounting system that can be discerned from the distinct way Balance Sheets were reported by Chinese Accountants between the “Great Leap Forward” and the “Reform and Opening Up.”

When Mainland China was united by the Maoists, there was an intense debate among Chinese Accountants on what sort of accounting system should be employed. Will the emerging Chinese Planned/Command Economy adopt Double-Entry Account Bookkeeping or the Soviet accounting system discussed previously? The latter was the obvious and natural choice because the early years of the People’s Republic of China saw significant assistance by Soviet Accountants within the Chinese Accounting Profession. It is perhaps even possible to interpret the debate among Chinese Accountants from that period as an analogue to the more prominent one among Chinese Economic Planners concerning Maoism and Dengism.

Traditional Chinese Accounting

To begin to understand how Chinese Accountants conducted themselves under the Maoists, it is important to realize that the Chinese Accounting Profession was not shaped by the same experiences as the Soviet Accounting Profession. Prior to the 20th century and China’s subjugation by European colonial empires in the 19th century, Chinese Accountants employed a traditional accounting system called “Sanjiao Zhang,” which roughly translates to “Tripod-Entry Account Bookkeeping.” This system appeared sometime in the 15th century, becoming the predominant accounting method in Mainland China prior to the Maoists and Kuomintang.

In its basic form, Sanjiao Zhang facilitated two things: the ability to oversee payments and the ability to track the movement of Currency for finished goods or services. A Chinese Accountant would record two sets of accounts for two specific events: economic activities where claims were made on the transfer of Currency for goods and services, the “Shou (Receipts),” and those involving typical transactional sales, the “Fu (Payments).” They would also omit sales and purchases made with Currency, recording them as separate entries with their own unified account. By Western accounting standards, Sanjiao Zhang resembled a combination of Single-Entry and Double-Entry Account Bookkeeping, hence the term “Tripod-Entry Account Bookkeeping.”

Later, the Chinese Accounting Profession devised another accounting system, “Longmen Zhang” (“Embankment-Account Bookkeeping”), that built upon the developments of Sanjiao Zhang. It still relied on the same methodology as Sanjiao Zhang, formalizing the Chinese accounting system into something more uniform and systematic for Chinese and Non-Chinese Accountants alike. Rather than a single “Financial Ledger” and a “Daybook,” like in Double-Entry Account Bookkeeping, the Longmen Zhang employed three different journals: the “Sales Journal,” “Miscellaneous Journal,” and “Purchases Journal.”

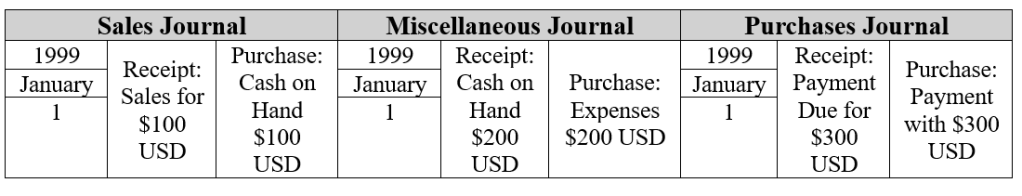

For ease of convenience, this Author has created the following chart to further illustrate how the Chinese accounting system functioned prior to the Maoists and Kuomintang. The chart depicts three different entries for three variations of a single event on January 1, 1999:

- The Sale Journal depicts how Revenue was generated on January 1, 1999, yielding $100 USD from a payment of $100 USD.

- The Miscellaneous Journal reports how an Expense was incurred for $200 USD, which was paid off with $200 USD.

- The Purchases Journal describes how a Payment of $300 USD was due on January 1, 1999 that was then paid on that same day with $300 USD.

It is important to note that, when the Maoists consolidated power in China after 1949, they abandoned the traditional Chinese accounting systems in favor of a modified variant of the Soviet accounting system. This can be easily discerned by the two distinct types of Balance Sheets that appeared prior to the Great Leap Forward and later during the Cultural Revolution. These Balance Sheets were given the appropriate designation of “Funds Balance Sheets” because how they fundamentally differed from the Balance Sheets employed in Double-Entry Account Bookkeeping.

Funds Balance Sheet prior to the Great Leap Forward

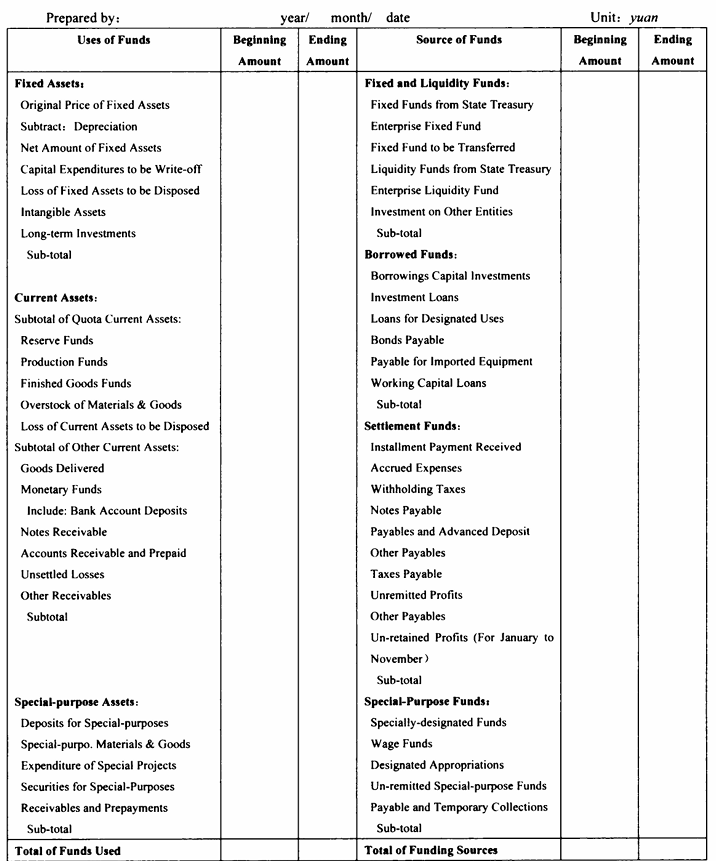

Based on Soviet accounting standards, the Maoist Funds Balance Sheet both prior to and during the Great Leap Forward was extremely detailed and comprehensive enough to be several pages long. The sheer length was justified by the Chinese Accounting Profession at the time to assist Economic Planners in overseeing the economic activities of entire Enterprises and Industries. It depicted, on one side, the Values of all existing Assets, and, on the other, the Values of all existing Liabilities. There were dozens upon dozens of individual accounts that Chinese Accountants needed to go over to articulate detailed descriptions to their Economic Planner counterparts. These accounts were then organized into five individual sections, each corresponding to a set of Assets and Liabilities, and each one given its own account code. There were five Sections in the Funds Balance Sheets prior to and during the Great Leap Forward.

Section I, labeled “Fixed & Accrued Assets and Fixed & Accrued Liabilities,” pertained to funds allocated to an Enterprise and everything that was owned by that Enterprise as part of its own economic activities. Section II, “Quota Assets and Quota Liabilities,” listed the Enterprise’s Inventories of finished goods and raw materials required for production processes. Section III, “Liquidation & Other Assets and Clearing and Other Liabilities,” are financial resources provided to an Enterprise such as the loans issued by State Banks, as well as all Accounts Payables and Accounts Receivables.

Sections IV and V are arguably the most interesting of the five Sections found in the Maoist Funds Balance Sheets from this period. Section IV, “Infrastructure Fund Assets and Infrastructure Fund Liabilities,” outlined the allocations of funds related to the construction of new facilities, and the installation of new equipment for the economic activities of an existing Enterprise. Section V, “Maintenance Project Assets and Maintenance Project Liabilities,” concerns the allocations of funds for the cost of maintaining and repairing an Enterprise’s facilities and equipment.

As one can probably surmise, this rendition was cumbersome insofar as it was a temporary design. Chinese Accountants realized that it would be practical long-term, regardless of whether the Great Leap Forward succeeded in achieving its goals. It was only during the Cultural Revolution that the Chinese Accounting Profession was able to successfully implement a simplified and respectable Funds Balance Sheet befitting of Maoism.

Funds Balance Sheet prior to Reform and Opening Up

The second rendition of the Maoist Funds Balance Sheet represented a further refinement and simplification of the earlier one prior to the Great Leap Forward. During the Cultural Revolution, it became increasingly imperative among Chinese Accountants to communicate more closely with their Economic Planner counterparts. What this meant is that a Chinese Accountant needed to be able to convey specific information about a given Enterprise to a Chinese Economic Planner. The former did not need to be versed in the Maoist version of Soviet-Type Economic Planning (STEP). Conversely, the latter did not need to be too familiar with the Maoist Funds Balance Sheet.

A typical Funds Balance Sheet during the Cultural Revolution would describe how much Currency was allocated from the State to a particular Enterprise at the beginning of an accounting period. The Chinese Accountant would write down that an Enterprise began the accounting period by receiving a fixed amount of Chinese Renminbi. They had to show where the Enterprise acquired any additional sources of funding besides whatever was allocated from the State. Next, they then needed to describe what the Enterprise had spent those sources of funding on and what was the result of those expenditures. By the end of the accounting period, the Chinese Accountant was expended to note how much the Enterprise spent and how much Enterprise generated from its own economic activities.

The general idea is that the Economic Planner, relying on the Accountant’s financial statement in the Funds Balance Sheet, will be able to ascertain what an Enterprise is doing with whatever was allocated to it. They can determine that the Enterprise had spent funds from the State as part of its production process, generating Expenses and Revenues in the process. The Funds Balance Sheet could then be used to make specific adjustments to how much an Enterprise is expected to receive from the State at the beginning of the next accounting period.

One ought to wonder why Mainland China no longer employs the Funds Balance Sheet after the Cultural Revolution. The reason has everything to do with the “Reform and Opening Up.” The rise of the Birdcage Economy, the Chinese “Socialist Market Economy,” stressed the need to adopt Double-Entry Account Bookkeeping to accommodate the coexistence of State and Social Enterprises with Private and Foreign Enterprises. China’s economic integration into the Empire of Liberty that the Jeffersonians had created through two World Wars necessitated its adoption. It remains an open question if the Chinese Accounting Profession would someday reconsider the Maoist Funds Balance Sheet because of its straightforward, yet comprehensive design.

This is an important question because the Chinese Accounting Profession, in contrast to the Soviet Accounting Profession, chose to adopt Double-Entry Account Bookkeeping with immense caution. Chinese Accountants had to familiarize themselves gradually in order to accommodate it. Soviet Accountants, meanwhile, were forced to quickly learn as part of the coinciding reforms of Perestroika, an event which did not bode well for both the Soviet Accounting Profession and the Soviet Union in particular.

Categories: Work-Standard Accounting Practices

Leave a comment